The Combinator

a speculative design fiction exploring a future with engineered babies

About this project:

Context:

SVA / 2017

Collaborators:

Type:

- Product Design

- Interaction Design

- Speculative

Design Fiction

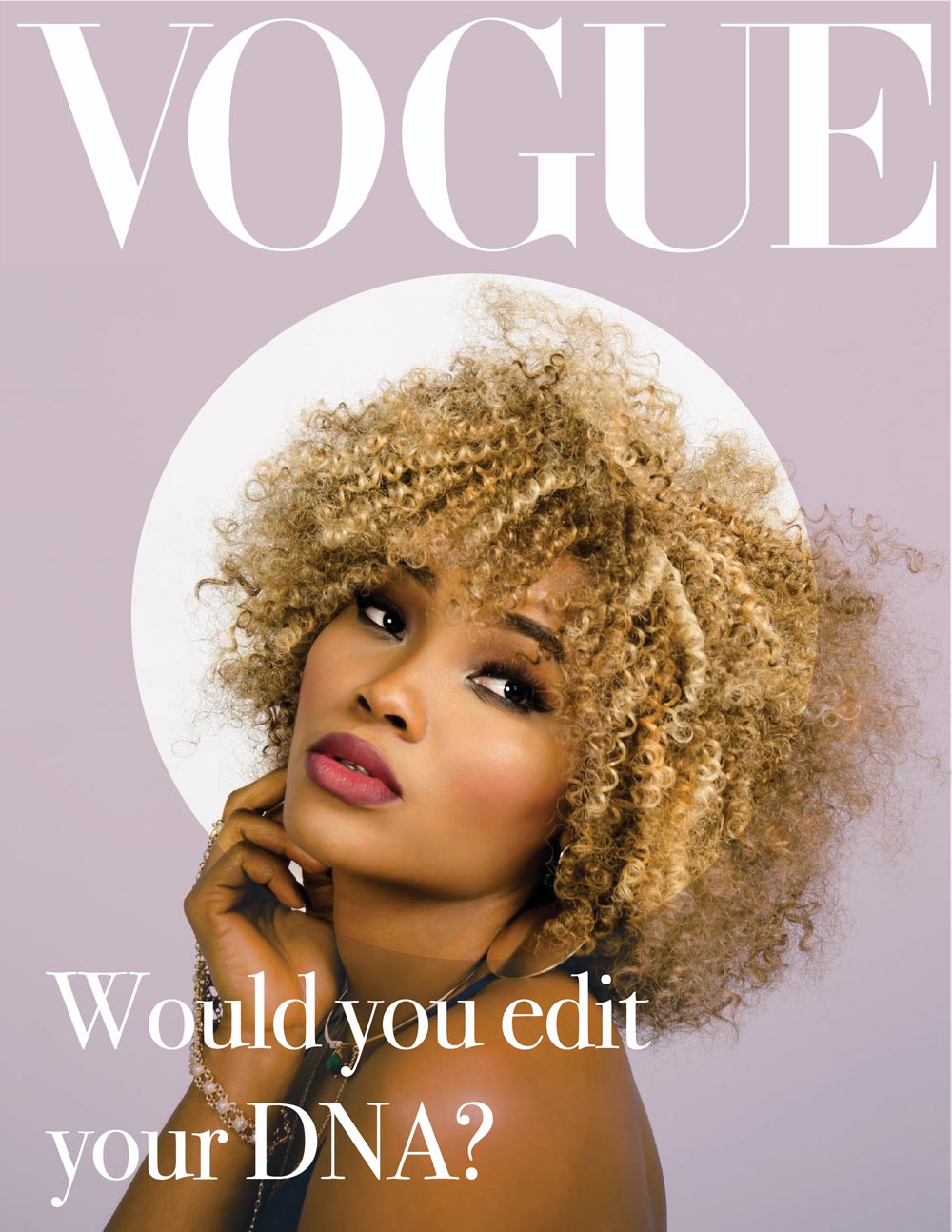

There's a lot of talk about CRISPR, the technology that makes gene-editing much simpler and cheaper. It has captured the imaginations of people heavily involved in biomedical science, journalists, and regular folk. The responses range from optimism—CRISPR will cure cancer, genetic diseases, viral diseases like HIV, while also giving us safe GMOs and superfoods and biofuels—to deep pessimism—CRISPR will give us crazy GMOs, bioweapons, and designer babies.

CRISPR is just the latest gene editing technology. It’s not necessarily CRISPR that we think is the big deal, but the way it has captured the attention of biologists and the imaginations of normal folks everywhere. CRISPR represents the ability to easily and cheaply modify human DNA to cure disease, and maybe throw in a few enhancements along the way.

Even though currently this technology is being used to understand and cure genetic disorders, we believe the future implications of this would be immense.

For this project, our team explored what impact technologies like CRISPR could have on our relationships with one another as people. We were most curious about how families would be affected once engineered births became the norm.

How CRISPR works

CRISPR doesn’t really do much by itself, but when paired with CRISPR-associated protein-9 nuclease (Cas-9) it has the ability to find any gene in DNA or RNA, break it apart, and replace it with something else.

CRISPR can be programmed to go through our genomes and identify specific parts that need to be changed. The Cas-9 is like a molecular pair of scissors that cuts those parts out. They are then replaced with either a gene delivered by the same CRISPR, or automatically regenerated by the host cell.

It's highly likely that by the time you're reading this, scientists will have improved on Cas-9 or found a better way that produces more accurate results.

Impact map

The implications of this are enormous. We can engineer food and animals, and even bacteria to create bioplastics and biofuels. We can target viruses like HIV and eradicate them. And we can edit humans.

This is where the ethics start to get a bit shaky. Editing humans will allow us to target genetic disorders such as muscular dystrophy. Edited human cells can be used to fight and eliminate cancer. The benefits are potentially huge.

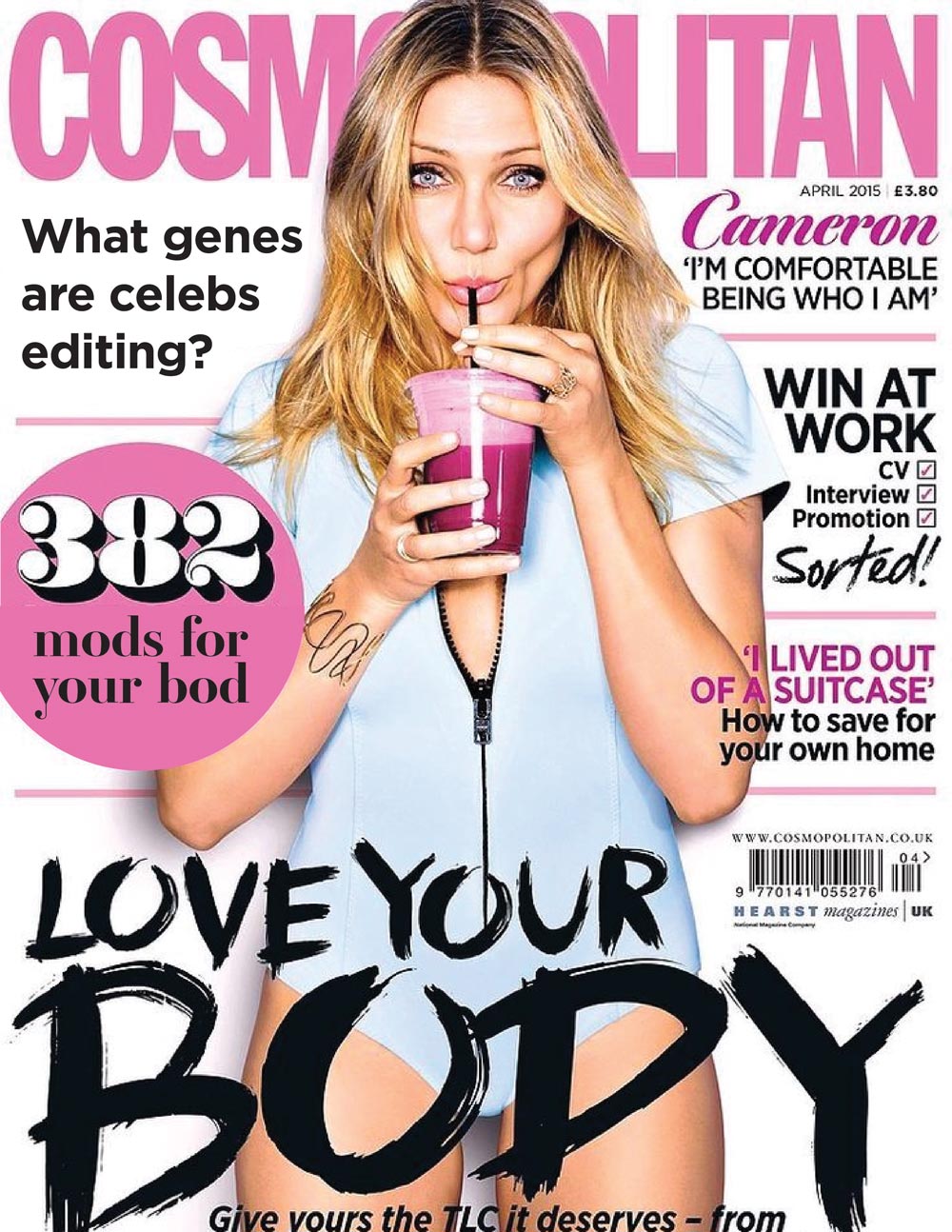

But we think this might be a slippery slope to other edits that humans might want to make. Why stop at eliminating hereditary disease when you can also increase the chances of a person being born with perfect vision, a high metabolism rate, and high levels of extraversion that will serve them well in their future careers? If you could choose, why wouldn’t you?

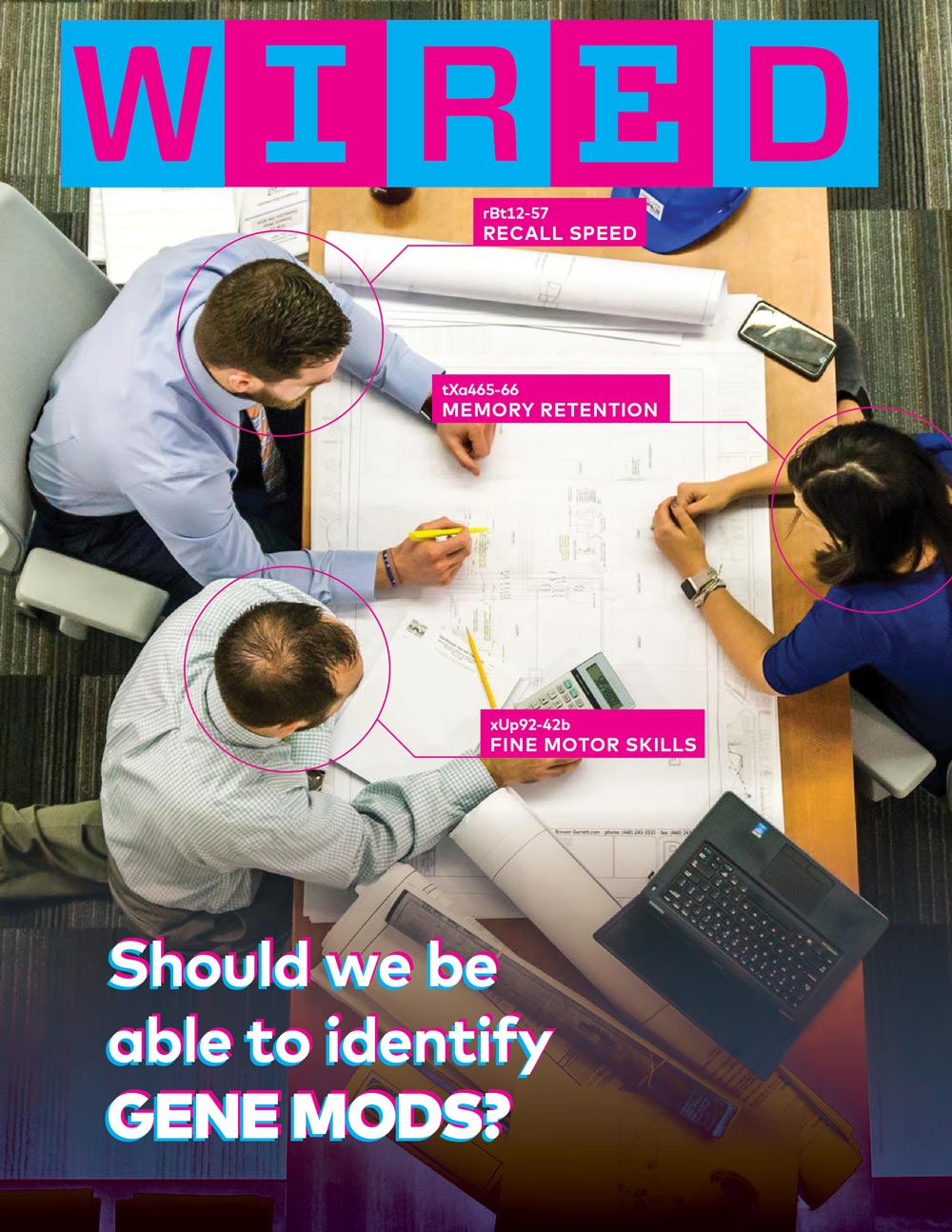

We think this will have an impact beyond just family planning: relationships will be viewed differently, government regulations will step in to protect human rights (or not), and hiring practices might even shift.

The Fiction

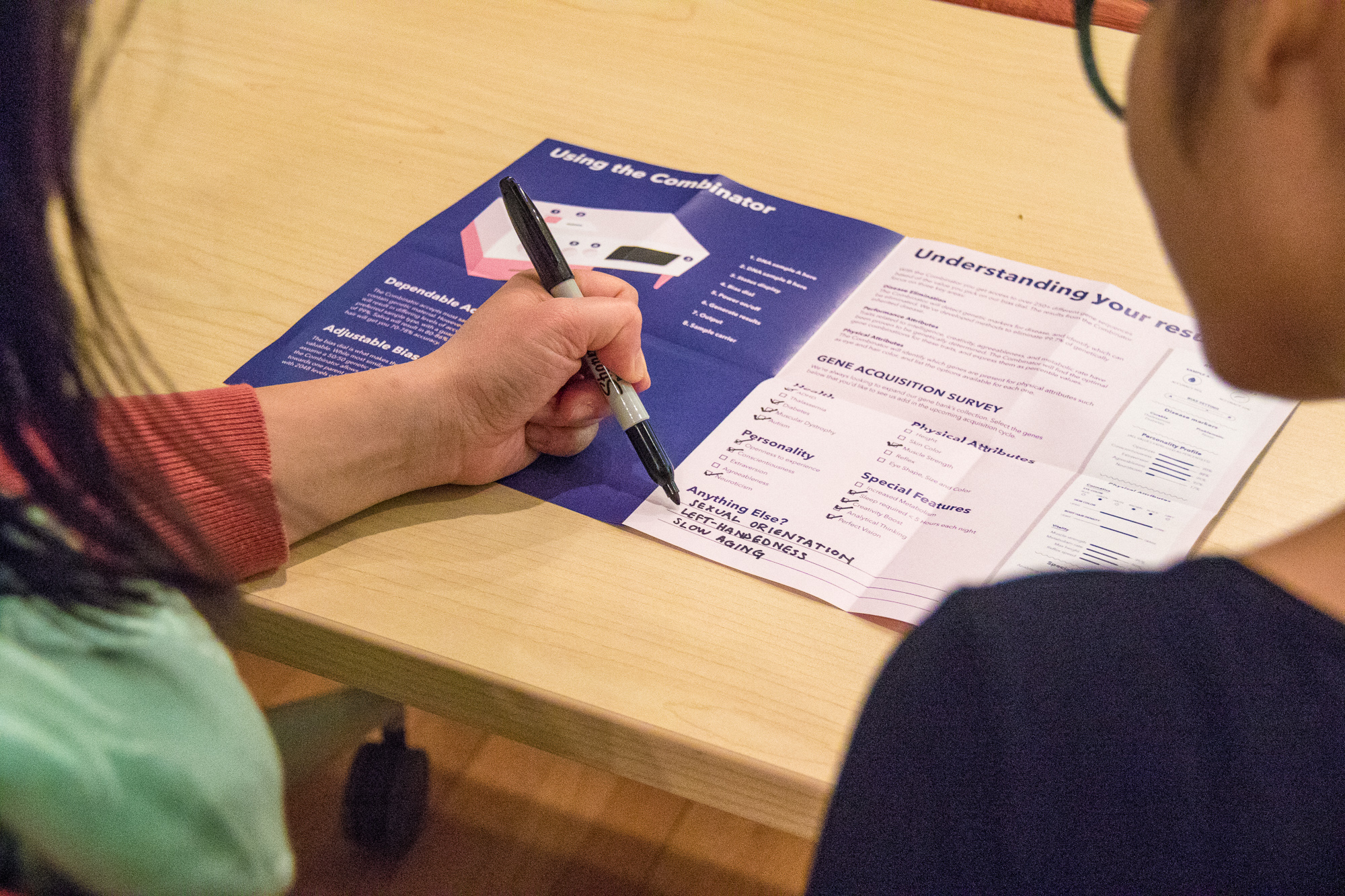

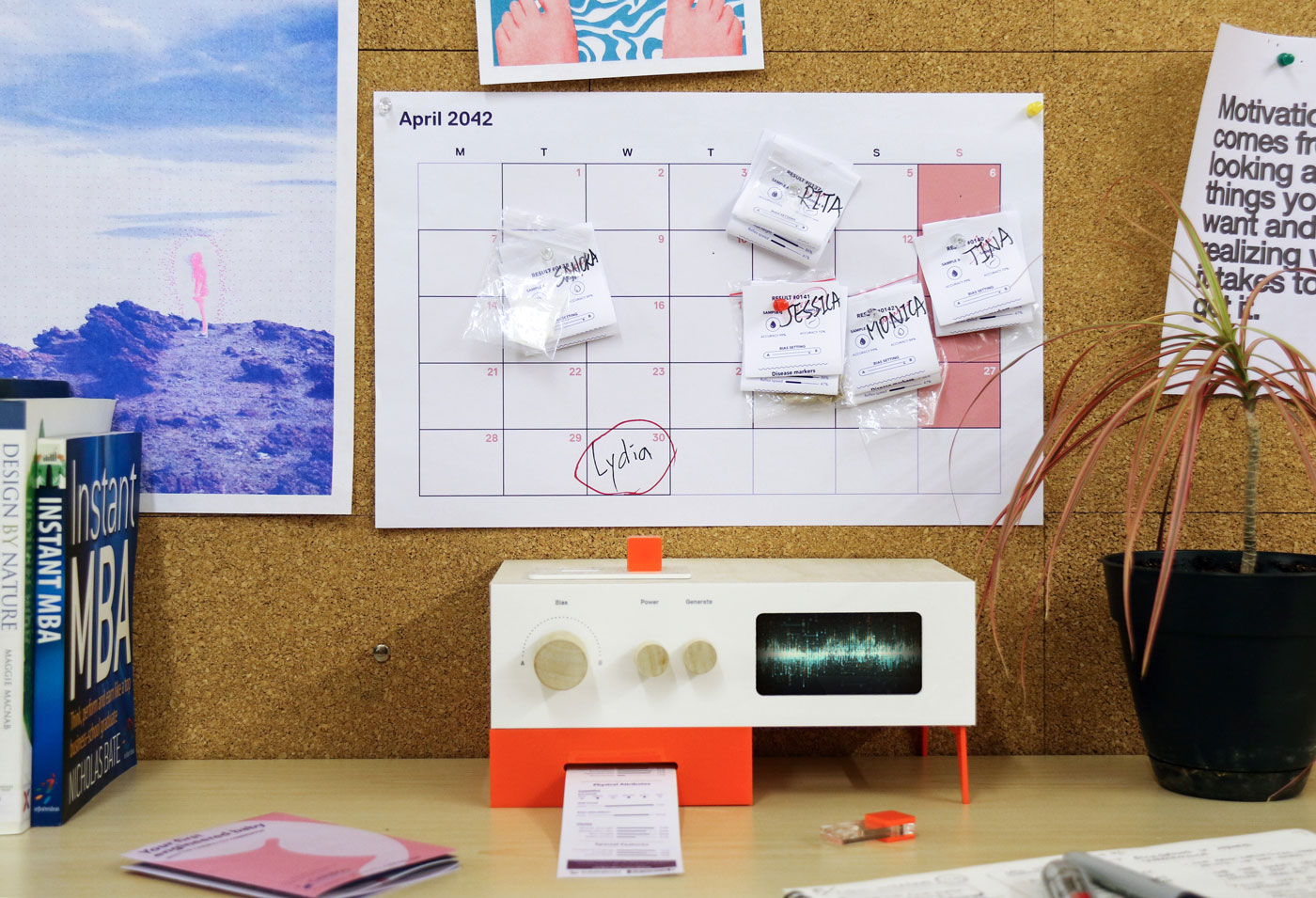

We explored some of these questions by imagining what family planning tools might become available in the age of genetically engineered pregnancies. We imagine the Combinator, a device that is readily available at your local pharmacy. The purpose of this product would be to analyze the combination of two samples of DNA to predict the possibilities available for an engineered pregnancy.

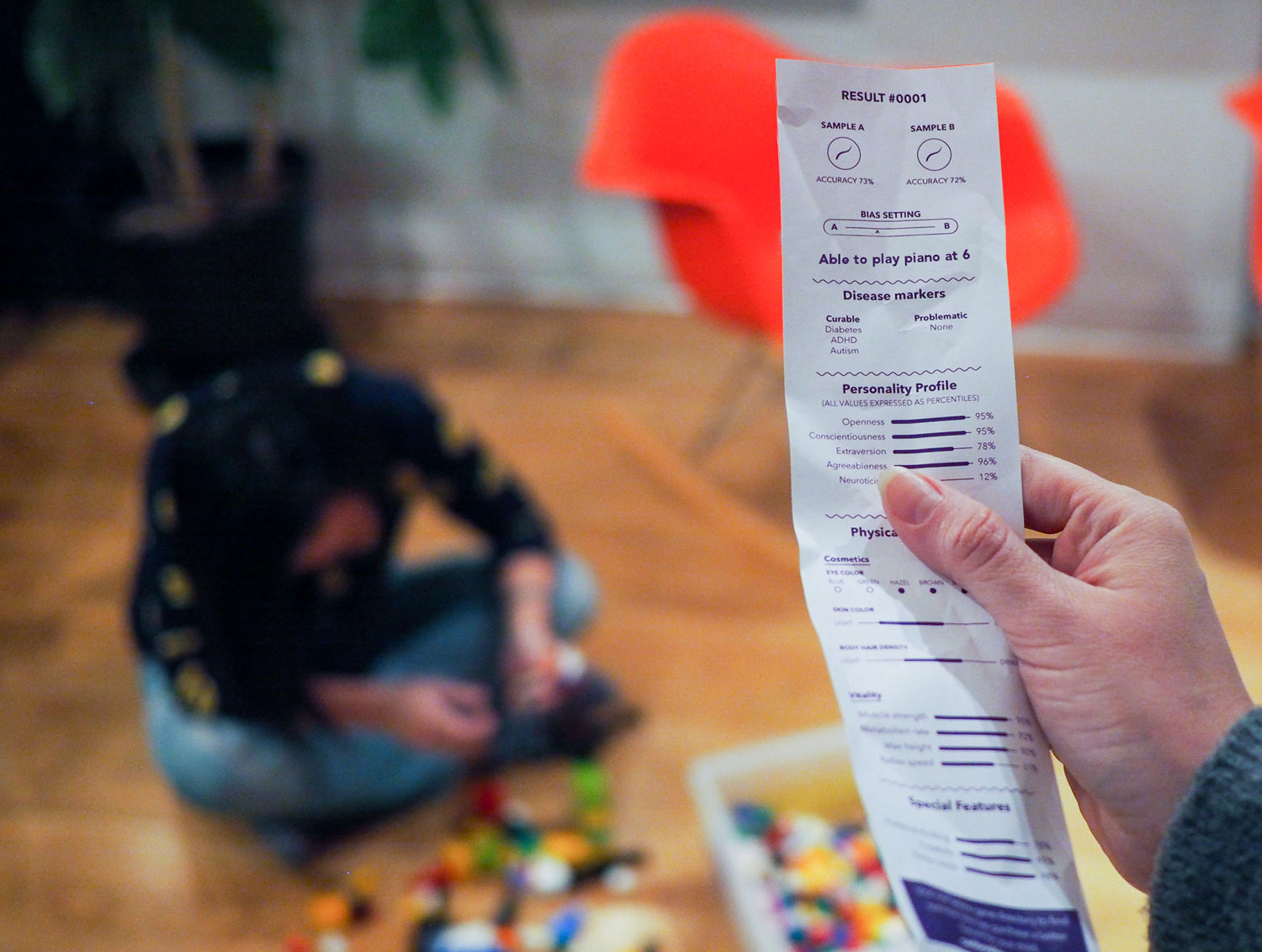

A couple could get this device, put in a strand of hair or drop of blood from each partner, and get a printout telling them what disease markers are present in their DNA and whether they’re treatable. Something like this sort of happens today, but after fertilization.

The device accepts different types DNA samples: blood, saliva, or hair. Blood will give you the most accurate results, and hair the least accurate.

We’ve made the device very simple, with only one setting: the bias dial. You can set the ratio of the genetic data taken form each sample by turning the dial left or right.

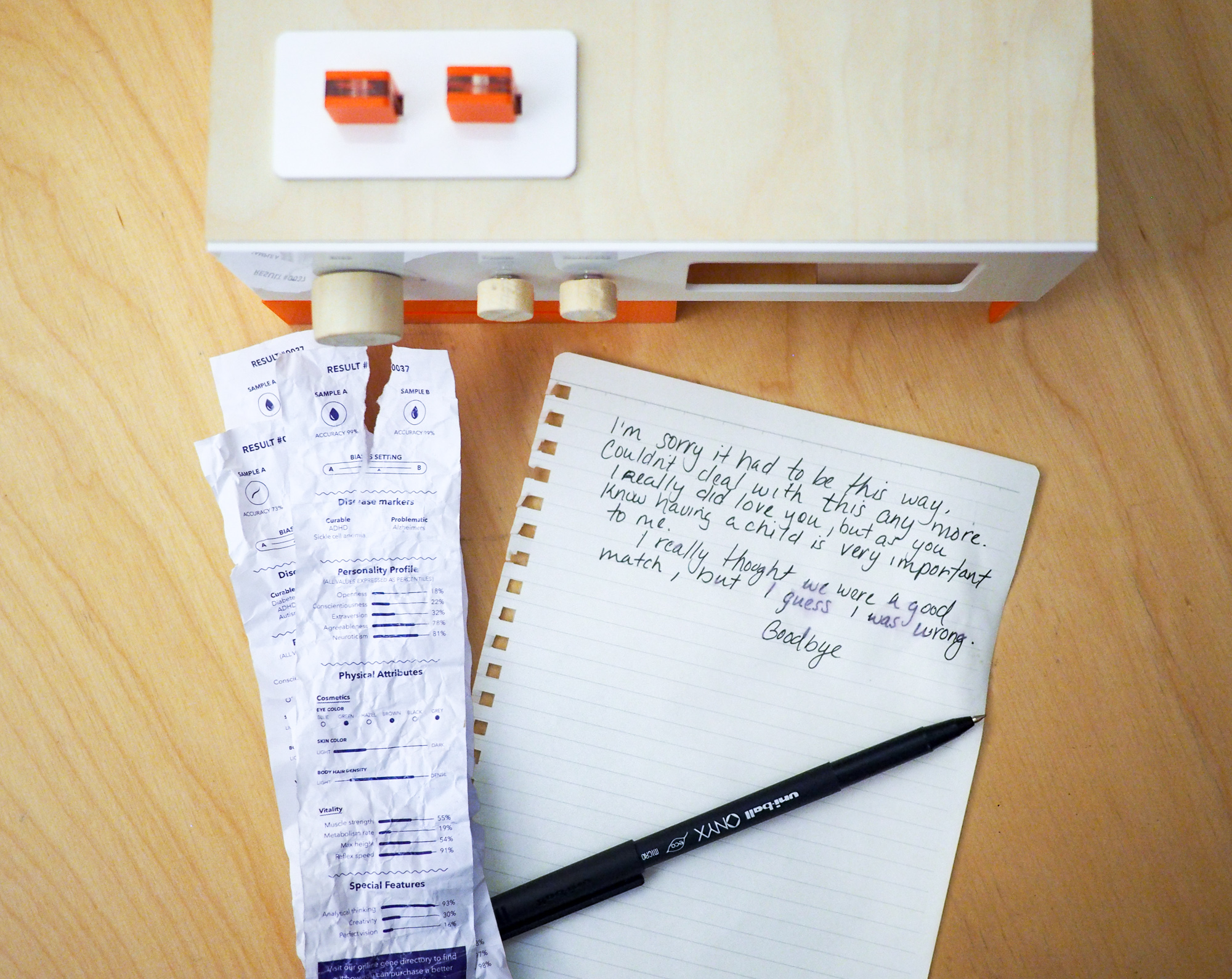

But what happens when the device keeps giving you results that you don’t want? What if with your partner, there is no avoiding alzheimers? Or if the combination of your genomes cannot produce a child that is above average?

What happens when the device promises you a child that scores well above average in all the desirable traits, but your child is struggling to perform in school and has a hard time making friends?

Or what if you are looking for that “perfect match”? Do you evaluate your dates based on genetic compatibility? Do you tell your dates that you’re doing this?

What gene edits should be off-limits? Should DNA testing be in the hands of everyone? Do you own genetic material that you find in public? Who should control access to genes?